The Look of this Heaven

In the age of digital photography, it always feels good to plunge back into the bright vividness of traditional film, capable, like no other medium, of capturing the bittersweet sense of long-gone days.

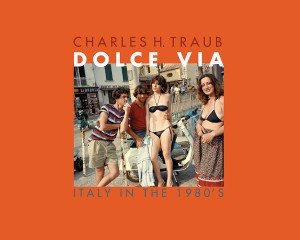

It is enough to browse through the pages of Dolce Via – a remarkable collection of shots taken by New York photographer Charles H. Traub in 1980s Italy – to breath the impalpable atmosphere of those years. After the economic and political crisis of the late 1970s, the country was then enjoying a second “economic miracle”. The rise of consumerism, the increase of leisure time and a new culture of entrepreneurship were prompting a re-discovered sense of individualism and widespread hedonism.

Traub was there, with his Plaubel Makina 67 and rolls of Kodak color negative film, to immortalize this cultural change. Rome, Naples, Venice, Capri, Taormina… Nothing escapes his keen gaze. Far from any cliché or postcard-like representation, he leaves the monuments in the background and focuses on the human side of the Italian street life, capturing the mute dialogue between living beings and inanimate objects, between the glory of the past and an unfathomable present.

As the book title suggests, Italy is no longer the place for Fellini’s Dolce Vita. The Trevi Fountain where Anita Ekberg took her legendary dip and called out for “Marcello!” 20 years earlier, more prosaically, becomes a place for passersby to rest and refresh themselves, and is used throughout the book more “as a kind of rhythmic device”, “a figure of punctuation” – says Traub – than as an iconic subject.

Attracted to the random, fascinating geometries of the bodies, he takes pictures of the crowds, and there he finds the solitude of the grumpy old man, the suspicious gaze of the young lady, the peaceful bliss of the reading woman.

He catches spontaneous gestures of intimacy, couples kissing or hugging on a bench, by the sea, in a half-deserted square. People rarely look at the camera. They are often caught in a moment of distraction. They gaze at something out of the frame, which is only left to the viewer’s imagination. Their poses are often clumsy; they bend down, lean forward, touch their feet, or are seen from the back. And when they look at the camera, they stare at us provocatively, an almost defiant smile hovering on their lips. Their bodies are far from being perfect, rather expressing the peculiar mix of decadence and beauty typical of most Italian landscapes.

In consonance with the pervasive hedonism of the time, as critic Max Kozloff points out in the Foreword, Traub’s street-life pictures bring out “the pleasure of the senses and of the flesh”. Young people in bathing suits or light summer dresses are indeed among his favorite subjects; they dominate their world with insolent vitality, powerful colors emerging from placid backgrounds.

The natural configuration of human bodies creates interesting games of perspective, as is evident in the photographer’s “striped shots”, where the intertwining of natural light, material artifacts and human actors gives life to new subterranean geometries and connections.

Whether it is a series of watermelon slices on display or the yellow dresses of two little girls, the chromatic quality of everyday objects stands out from the Italian urbanscape.

The motivation behind his pictures is made explicit in the final dialogue between the street photographer and his muse, written by dramatist Luigi Ballarini.

Filtering through the contrast between light and shadow, youth and age, sacred and profane, is the idea of an impossible resurrection: “Italy looked to me like a dystopia whose inhabitants acted as if they were living in heaven”, says Traub. It is exactly this inborn indolence, this combination of “fatalism and total inaction”, that still seems to permeate the Italian way of life.

In his fresco of the 1980s Italy, Traub definitively meets the challenge of revealing “the uncanny” in apparently ordinary situations, re-framing the world he saw before him and giving a fresh insight into the soul of this enduringly appealing country.

Laura Giacalone is the Associate Editor for the Italian Journal