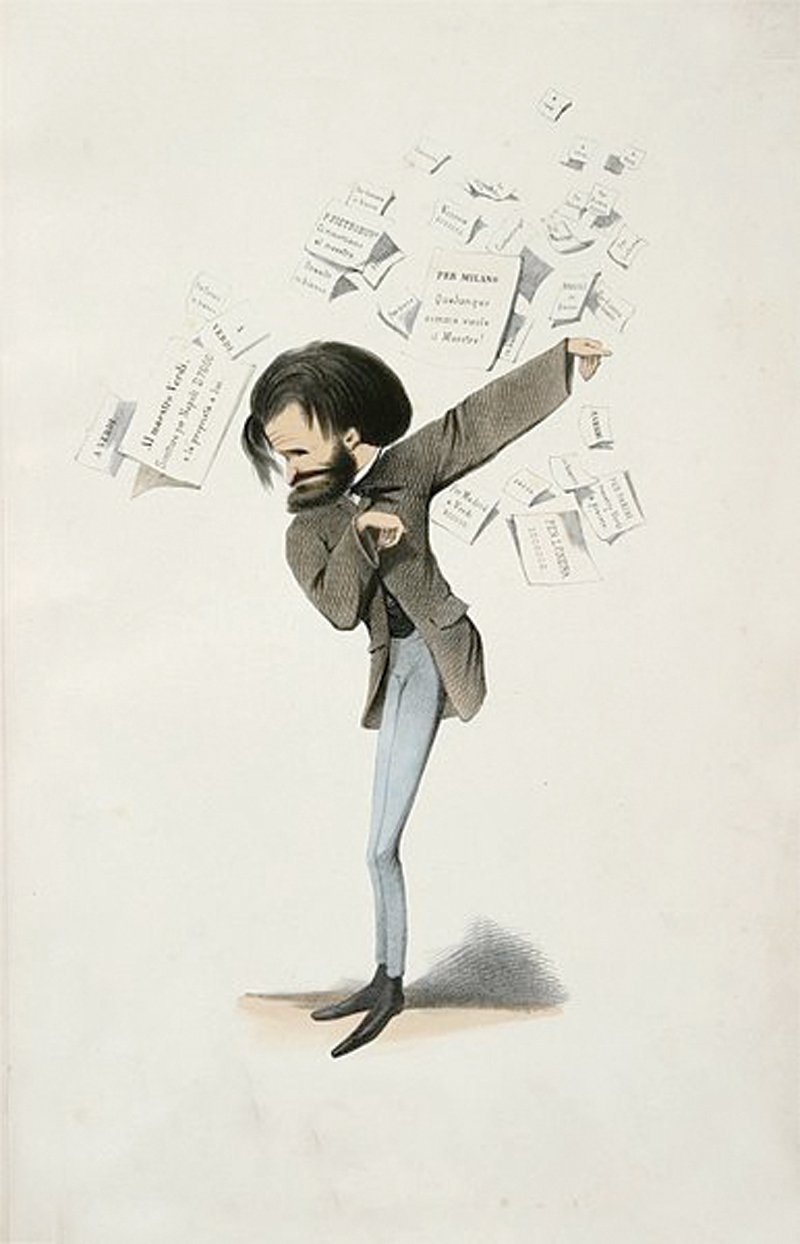

Verdi

Resounding Influence

by George W. MARTIN

As he enters his two hundred and first year, Verdi continues to hold the interest of American scholars and the affection of a vast audience. The scholars, responding to the “Verdi Renaissance,” which began in Germany in the 1920s and reached the United States in the 1940s, after gorging for half a century on Wagner rediscovered Verdi. Learned articles began to appear, symposiums were held, and world congresses hosted. In 1976 the American Institute for Verdi Studies was founded, a journal started, original material gathered, and the world’s largest archive of microfilmed material on Verdi collected. Then in 1983 the first volume of a critical edition of his works was published. Devoted to Rigoletto, it was primarily the work of American scholars. And all this proceeds apace.

As for the affection of audiences: Though other composers — say Bizet, Puccini, Mozart, or Mascagni — may have one or even two operas that receive more performances in a year than any one of Verdi, none can match his mass. He composed twenty-six operas (twenty-eight if two revisions with changed plot and title are counted), and in mid-summer 2013, when some 100 U.S. companies announced their schedules for 2014, these listed productions of sixteen of the twenty-eight operas. Moreover, to these sixteen some companies outside the U.S. added five more, so that in a single year, with all companies not yet reporting, Verdi will have at least twenty-three of his twenty-eight operas performed.

Such a figure is possible only if audiences step up to the box-office and buy. Which raises a vital question: What is it in Verdi that people like? Curiously, the question is not much asked by scholars. They tend to focus more on technical matters, such as Verdi’s key structure, his handling of coloratura, revisions in orchestration, work on the libretto, and problems with censors or with the librettist. So, what is it in Verdi that appeals to audiences?

A brief answer, for much of it is conceded, surely would include the following. First, as was noted as early as 1859 by an Italian critic comparing Verdi to Donizetti: “Verdi, as the more passionate, strives more often to agitate and excite the audience; whereas Donizetti strives almost always to delight it.” It seems so. Verdi steadily increased his skill at luring audiences to participate emotionally in the drama onstage, to see in its characters some traits of their own, so they come to empathize with the protagonists, whether good or bad. Consider, for example, how he hones this skill from Nabucco to Macbeth to the finale of Rigoletto where he successfully moves his audience to sympathize with a man who is truly more bad than good. In sum, compared to Donizetti Verdi offers drama not concert.

Allied with this skill is another of theatrical pace. It is often said that:“Verdi plays better onstage than he reads in the score.” And it is true. On the page the reader doesn’t gather as well as in a theatre, sharing with others beside him and onstage, the sense of acceleration, the increasing momentum, the rush to the inevitable end. Even as Violetta in Traviata announces she will live, wants to live, the audience knows she will die. And when she does, Verdi brings the curtain down swiftly, so that the shock of her death remains in the air even as the audience applauds.

Furthermore, all of Verdi’s operas are about humans — no gods, dragons, rings of fire, or scenes in hell or heaven, no drifting through myth into an unreal world, but each opera anchored in common experience. With greater or less success he portrays fellow humans confronting harsh dilemmas, trapped in awkward decisions in which they suffer. And for such stories, human stories, there will always be an audience.

Moreover, in Verdi men and women are always responsible for their acts and choices. Though fate may be against them, for each there is an area left for choice, and choose they must. Anyone wanting to hear an opera in which society is blamed for all that happens will not hear it in Verdi. In Traviata, perhaps the most frequently performed of all his operas, Violetta makes her choice; and suffers for it. That view of our condition — that we may not be able to control our fate but we can control our response to it, noble or unworthy — is likely always to find an audience.

Lastly, and perhaps most appealing to audiences, is his gift for melody. Melody has extraordinary powers. Scholars have shown that even in places where the text has become garbled and no longer makes sense, the melody alone can deliver the singer’s meaning: I’m in love; I hate; I die. Thus when the Count in Trovatore sings of his love for Leonora, even though non-Italians in the audience may not understand the words, they grasp the emotion. Additionally, melody in the theatre can create an extraordinary sense of community between stage and audience, fusing a thousand individuals into a single responsive unit. And few if any composers have matched Verdi’s ability to sum up a dramatic situation with a short, piercing melodic phrase, such as Aida’s cry, “Numi, pietà.” It is simple, heart-rending, and draws audiences immediately into her dilemma.

Will Verdi in the coming years dominate the operatic repertory as he does today? If another composer soon appears who can tap successfully into Verdi’s strengths, then audiences will want to hear the new stories and music; and the repertory will adjust, cutting back on Verdi. But if no such composer appears, then possibly audience will continue to hark back to him, for in his dramas he celebrates values they cherish and in a manner they like. In which case, even at his tercentennial, he will still be heard.

About the Author

George W. MARTIN

Born in New York City, which he calls “home”, George Martin practiced law there for five years and then quit to write books full-time. Some of these have been about opera, especially Italian opera, especially Giuseppe Verdi. Of these his most recent is Verdi in America, Oberto through Rigoletto (2011) — on the reception of the operas in the United States; on how opinion formed, sometimes changed, and when, how, and why. Others have touched on New York and U. S. legal history, of which the most recent is CCB, which won the Griswold award of the Supreme Court Historical Society, 2006. See: www.georgewmartin.com.

Born in New York City, which he calls “home”, George Martin practiced law there for five years and then quit to write books full-time. Some of these have been about opera, especially Italian opera, especially Giuseppe Verdi. Of these his most recent is Verdi in America, Oberto through Rigoletto (2011) — on the reception of the operas in the United States; on how opinion formed, sometimes changed, and when, how, and why. Others have touched on New York and U. S. legal history, of which the most recent is CCB, which won the Griswold award of the Supreme Court Historical Society, 2006. See: www.georgewmartin.com.