Transcending the Appenine Divide: Italy’s mountainous terrain affects its socio-political history

American high-school students often come away from a basic course in European geography believing that the Alps are the only major topographical feature to note in Italy’s landscape. Having studied the epic crossings of Hannibal and Napoleon, they are left with the impression that it is “all downhill from there.” I was reminded of this recently while helping some friends arrange a road trip from Rome to San Giovanni Rotondo. Much to their chagrin, they discovered that there is no “direct route” from point A to point B since a mountain range – namely the Apennines – runs down the middle of the country.

Notwithstanding their majestic beauty, the Apennines are a major complicating factor in the story of Italian unity. In fact, only about one fifth of the land is classified as plain (pianura), and most of that area is concentrated in the North Lowland. While the Alps and surrounding seas constitute natural boundaries that clearly designate Italy as a geographical entity, the Apennines subdivide her into a collage of regions and peoples. They form a single, serpentine chain, varying in width and running over 1,300 miles from the extreme northeast to the west, curving to Liguria, extending southeast, heading south through the peninsula, and finally stretching from east to west across northern Sicily. While this tortuous course has been the cause of disagreement among geologists about how best to divide Italy into physiographical regions, it does explain why the peninsula has rarely served as a bridge for travel between northern Europe, Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean.

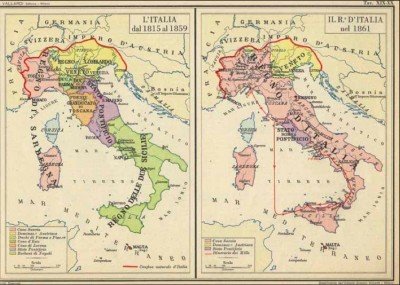

The mountains have not been without their political effects. From the collapse of the Roman Empire in 410 until the Risorgimento, Italy was a myriad of loosely connected communes frequently subjected to invading powers. A general division began to emerge in the 12th century, corresponding roughly to the frontier between the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Sicily. Beginning in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the feudal character of the south was solidified while the north enjoyed spectacular agricultural development, a burgeoning industry, healthy trade and an urban culture. Although economic expansion in the north slackened during Spanish and Austrian domination, the south was never able to catch up. Moreover, the administrative structures of the Austro- Hungarian Empire left an indelible mark on the north – especially Lombardy and the Veneto – while the south retained traces of social stratification bequeathed to it by the Spanish Bourbons whom Garibaldi finally sent away in 1860. Rome, relying on a long pedigree of papal rule, remained aloof to both.

For many centuries the Apennines thwarted communication between east and west, stymied trade and discouraged the use of common currency, weights and measures. This makes Italy’s story of unification quite different from a nation like Germany, whose economic unity paved the way to political unity. Having no such basis, Italy had to rely on the avant-garde aspirations of Mazzini, Cavour and Garibaldi, all of whom were ultimately disappointed by the people’s lack of readiness to embrace republican values. Neapolitan historian Luigi Blanch foresaw the difficulty in 1851 when he wrote, “the patriotism of the Italians is like that of the ancient Greeks, and is love of a single town, not of a country; it is the feeling of a tribe, not of a nation.”

This sense of apathy greatly abated during the economic success of the postwar period, convincing many citizens that the country was free to write its own history by relying on the ingenuity, entrepreneurship and work ethic of its own people. Italy quickly attained the status of a functional, centralized modern state, relegating regionalism to local traditions and social attitudes. Indeed, despite her topographical variety, Italy’s population is evenly distributed and highly aggregated. In Apulia and Sicily, most people live in demographic centers numbering over 10,000 inhabitants.

Unfortunately, the influence of the Apennines on Italian history has not been written by Mother Nature alone. Deforestation has had a devastating effect on agrarian sustainability in the south. When the Greeks first arrived in the eighth century, they encountered rich forests stretching for miles across the peninsula. Oak, ilex, laurel and myrtle on the heights of Calabria’s mountains still give us a sense today of what they must have found. Chopped for cash and fuel, these trees once drew throngs of settlers to the peninsula. Depletion of forestland eliminated a natural defense mechanism against landslides and erosion, exacerbating the effects of heavy rain and earthquakes. Whereas wheat and corn cannot withstand erratic weather patterns, trees thrive. The swamps resulting from deforestation also gave new breeding ground to the anopheles mosquito, spreading malaria until the use of DDT in the 1940s.

How a country’s topography affects its history is not beyond human control. Deforestation is but one example. The anniversary of Italy’s unification is an occasion to reflect on her unique geography and the impact it has had on her social and political life. At the turn of the 19th century, a political realist like Klemens von Metternich (1773-1859) could easily say that “Italy is only a geographical expression”. Yet as we enter the 21st century, it is clear that Italy’s geography is more than an expression; it is an integral part of her identity. Seas both separate and connect. Mountains distinguish and bind. The former has created Italy, and the latter “Italians.” It is no accident that family and town continue to be primary reference points for understanding who one is as an Italian.

At the same time, to be an “Italian” increasingly means to live with and among “Italians” who are neither from your family nor from your hometown. In a recent video-teleconference, I connected with colleagues from Milan, Bergamo, Brindisi, and Taranto. We exchanged ideas on a nation-wide pastoral initiative from four different perspectives based on experiences in four different local churches. We then discovered that young people from all four dioceses were in need of lodging in Rome for the May 1st beatification of John Paul II. Once connection led to another, and we were able to make arrangements within 24 hours. That was all I needed to convince me that unity-indiversity – created by the Apennines – remains Italy’s greatest challenge for today and promise for her future.

About the Author

Monsignor Daniel B. Gallagher is a priest of the Diocese of Gaylord (U.S.A.) currently serving in the Latin Section of the Vatican Secretariat of State in Rome. Prior to this assignment he taught philosophy and theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, Michigan. His recent articles have appeared in Sacred Architecture, Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Quarterly, New Oxford Review, Josephinum Journal of Theology, and other scholarly publications. Cultivating a keen interest in aesthetics, Msgr. Gallagher frequently reviews art exhibitions in Rome and throughout Italy for The Berkshire Review. He regularly contributes to the “Philosophy and Popular Culture” series and edits the “Values in Italian Philosophy” (Rodopi Press) series which is dedicated to offering the English-speaking world works by classic Italian thinkers as well as books in contemporary Italian philosophy.