The Double Fugitive: The artist, simultaneously revered and exiled throughout his life

When on 6 October 1608, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, a Knight of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, Rhodes, and Malta, escaped from detention in Fort St Angelo on the small Mediterranean Island of Malta, he became Malta’s most wanted fugitive. Ironically, his arrival on the island some 14 months earlier was also that of a disgraced fugitive, of a person who was trying to rebuild his career and social standing through an impressive network of protectors (1). He had escaped from Papal Rome after murdering Ranuccio Tomassoni and after finding refuge in the Colonna estates and in the city of Naples, he sought to try his fortune with the Knights of Malta. In moving out of Rome, surprisingly deciding to go South rather than North, he also shaped the character of South Italian early seicento painting. The artist’s search for new patrons and protectors, his patrons’ desire to have him in their service and the misdemeanors of his lifestyle will impinge on the character and spread of Central Mediterranean Caravaggism.

The story of Late Caravaggio is that of a fugitive who produced some of the most powerful pictures of the entire century. He was constantly on the move and, in many instances, looking over his shoulder. It was precisely this movement from “place to place,” conditioned by the fast-pace lifestyle of Caravaggio, that also brought about the fast spread of Caravaggism in the central Mediterranean, and specifically south of mainland Italy, on the islands of Sicily and Malta. After Malta, the man was a ‘double fugitive.’ Bellori brilliantly captured the artist’s complicated context in Sicily and summed it up as follows: Ma la disgrazia di Michele non l’abbandonova e il timore lo schiacava da luogo in luogo (2)

The story of Late Caravaggio is also that of powerful patrons who sought to protect him despite knowing very well that he was a fugitive and despite being very well aware that such protection could lead to diplomatic consequences. This is what happened respectively in Naples, Malta, Syracuse, Messina, Palermo and, once again, Naples. Wherever he went, the artist was honoured and protected. Patrons were more interested in securing his brush rather than handing him over to justice.

Caravaggio’s transfer to Malta and, thereafter, to Sicily is one of the most brilliant chapters in the history of art of both islands. As a fugitive from Papal Rome, the artist first arrived in Malta in mid-July 1607. The powerful current of Realism that had taken Rome and Naples by storm and surprise was now to surprise Malta. Fifteen months later, in a dramatic shift of events that culminated early in October 1608, the artist fled the island as a disgraced fugitive. The Maltese period was a milestone period in the exciting context of Caravaggio’s late years. It was a period when Caravaggio, a fugitive yearning to return to Rome, produced outstanding masterpieces that ironically only a handful of the great artists of the younger generation saw.

Away from the swarming verve and crowded commotion of a sprawling Naples, the compact and fortified city of Valletta, so different and so small in comparison, became a haven for the artist. He was far away from his artistic and personal rivals, and had thus every opportunity to peacefully reflect on his art and seek important political alliances that would help him achieve his ultimate objective of setting foot once more in the Papal capital.

Within the knights’ palaces in Valletta, Caravaggio’s former patrons in Rome were well known and news that Caravaggio was in the city would have spread fast. Caravaggio’s Italian admirers would have known that he was in Malta and would have been thrilled by the audacity of his unpredictable move. In the austere but cosmopolitan context of Valletta, Caravaggio probably believed that powerful patrons and good fortune would eventually bring him politically closer to the Papal court. Yet, as much as he had this search for greater protection and security in his mind, he probably also dreamt of chivalry and knighthood and of wearing the black habit with the white eight-pointed cross over his shoulder; this was the image of him that Giovanni Pietro Bellori would present in his famous portrait print for Le Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni published in Rome in 1672.

The artist’s Maltese period is largely concerned with his knighthood, that is, his ambition for it, his arming, and disrobing. From the onset, the artist should have known, however, that the statutes of the Order of St John prohibited the reception of those guilty of murder and certainly he would have realized that this was a great obstacle that needed to be overcome. His virtuosity was his only asset; he knew well enough that it was a source of attraction and that he could benefit by astonishing his patrons with the realist and naturalist power of his art. This was the onset of Caravaggism in the South (3).

In Valletta, Caravaggio attracted around him prominent personalities and his circle of protectors grew to include new patrons. Amongst his patrons was the Grand Master himself, Alof de Wignacourt, for whom he painted a full-length portrait accompanied by a page (Louvre, Paris). The others included Fra Francesco dell’Antella and Fra Ippolito Malaspina, for whom he painted the easel pictures of the Sleeping Cupid (Palazzo Pitti, Florence) and St Jerome (St John’s Museum, Valletta). A further patron – probably rather than securely – was Fra Antonio Martelli, who is likely to be the person painted in the Portrait of a Knight (Palazzo Pitti, Florence). For the Lorraines he executed, probably in Malta in 1608, the altar painting of the Annunciation of the Virgin (Musée des Beaux Arts, Nancy).

Soon the knights of Malta recognized the benefits that they could reap from Caravaggio’s presence and thus offered him a prize that was hard to refuse. This was the prize of knighthood, a bold move which secured an even more intimate connection between artist and patron.

The reception ceremony at which Caravaggio was invested with the habit of a knight of magistral obedience was held in St John’s conventual church (now co-cathedral) in Valletta on July 14, 1608. On that day, the city crowned the most famous artist in the western world and embraced the new Naturalist style. Admiration for Caravaggio’s work was deliberately spelled out at the reception ceremony, as also were the expectations that this

Naturalist style was to be a vehicle for the glorification of the knights of Malta. “We wish to gratify the desire of this excellent painter, so that our Island Malta, and our Order may at last glory in this adopted disciple and citizen” (extract from the document of Caravaggio’s investiture) (4).

Caravaggio became the Knight’s official artist. Young artists were expected to follow his style.

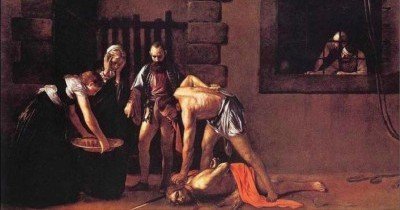

Given the amount of time that Caravaggio spent on the island (July 1607 – October 1608), the corpus of pictures dating from Malta is undeniably small, but they are milestone pictures which perfectly sum up his Maltese temperament. The vastness of the Beheading of St John the Baptist, spread out on an enormous canvas in the Oratory of S. Giovanni Decollato, was a challenge that Caravaggio probably set out himself. It was a scale that was more appropriate to mural painting, a scale that he had never ever previously attempted. He applied his finishing touches to it as a knight of Malta and thus proudly signed his name as Fra Michael Angelo, painted in the blood oozing from St John’s head. This was the most impressive moment of Caravaggio in Malta, a picture made as an expression of virtue.

Barely four weeks after his elevation to knighthood, the artist was involved in a serious brawl in Valletta during which a senior knight was badly injured (5). This biographical episode was, once more, to have a decisive impact on the eventual spread of Caravaggism. The sudden drama of the brawl in Valletta in August 1608, subsequent detention in September, and his break-out in early October, meant that Caravaggio’s Maltese period was over. He was apprehended and detained in Fort St Angelo, an imposing old fort situated on the other side of the Grand Harbour. Caravaggio’s break-out from this fort, incredible as it still seems, took place in early October. Once again, he was on the run. After Malta, disgraced and still a fugitive but not at all secretive about his whereabouts, the restless Caravaggio was in Sicily moving between Syracuse, Messina and Palermo, spreading out – perhaps unintentionally – the power of his style. Syracuse, Messina and Palermo were to become centres of Regional Caravaggism.

That there was an ‘arrangement’ to help Caravaggio escape is clear but it is difficult to ascertain who helped him. In an island of informers and of rewards for information, it is significant that nothing came of the investigations, except that he used a rope. Escaping from the Convent was, as already noted, a dishonourable deed, and a dangerous one too. Moreover, everyone in Malta knew that, in such circumstances, even the fugitive’s accomplices risked a great deal. If who helped Caravaggio were knights, they risked the privatio habitus. If secular – as I believe – they were even in greater trouble, and liable for punishment. From other documented instances, it clearly emerges that the Grand Master wanted fugitives back in Malta (6). This would have been the situation which faced Caravaggio after his escape, and Bellori himself records that Caravaggio feared that the knights were after him. Caravaggio was well aware of how Wignacourt treated those who contravened the Statutes. Moreover, throughout his first weeks in Sicily, the galleys of the Order were sailing off the harbours of that island, in both Siracuse and Messina.

In Sicily, the members of the Senate of Syracuse probably could not even believe their luck and thus moved immediately in order to protect him. One of the most famous and certainly the most talked about artist of their time was in predicament and in their city seeking protection. At this stage, the Senate’s options were simple. They could either apprehend the fugitive criminal and duly send him back to neighbouring Malta, as it was their obligation to do so, or seek to secure his services for the city. Their choice was the latter. They made no secret about it and stretched one of their largest canvases for Caravaggio to execute an altar painting of none other than St Lucy , the patron saint of the city. So powerful, indeed, was the allure to Caravaggio’s art.

The Knights’ Receivers in Sicily should have certainly been well informed about Caravaggio’s escape, but it is still not clear why they did not manage to move “with secrecy” in order to apprehend him, as they had done in other instances. Perhaps this was because Caravaggio managed to insert himself into and enjoy immediate protection. It is obvious that Caravaggio had moved well and that, for the Order, his apprehension could have become an embarrassing affair and, in such circumstances, it seems that it would have been difficult for the Order to expect official help from the Sicilian cities.

In painting the dramatic Burial of St Lucy, the Beheading of St John the Baptist was still fresh in his mind and the same personages, painted from memory, returned. The jailer was now the man holding a handkerchief next to his face, whilst the old lady now knelt in grief with her hands on her cheek.

The remaining months of Caravaggio’s career were, geographically and politically, marked by his moves towards the much wanted return to Rome, a return which could only be made possible if his protectors managed to pledged in his favour with Pope Paul V. His story with the Knights of Malta was over by December 1608 when they unceremoniously stripped him of his habit and thus deprived him of his knighthood in abstentia. The artist who only six months earlier was heralded by the knights as their new Apelles, and whose signature as Knight of Malta on the Beheading of St John had barely dried, was rejected and cast away, “just like one casts away a rotten and fetid limb” (7).

Endnotes

1 For Caravaggio in Malta see, amongst others, J. Azzopardi, Caravaggio’s admission into the Order: Papal Dispensation for the Crime of Murder, in Caravaggio in Malta, ed. P. Farrugia Randon, Malta, 1989; S. Macioce, Caravaggio a Malta e i suoi referenti: notizie d’archivio, in ‘Storia dell’arte’, LXXXI, 1994, p. 207; K. Sciberras, Riflessioni su Malta al tempo di Caravaggio, in ‘Paragone’, Anno LII N.620 Terza Serie 44, 2002; K. Sciberras: ‘Frater Michael Angelus in tumultu: the cause of Caravaggio’s imprisonment in Malta’, in The Burlington Magazine 144, 2002; K. Sciberras, D.M. Stone, “Caravaggio in black and white: art, knighthood, and the Order of Malta (1607–1608),” in Caravaggio, The Final Years, ed. N. Spinosa, exh. cat. (London: The National Gallery; shown earlier at Naples, Museo di Capodimonte), Naples, 2005; K. Sciberras, D. Stone, Caravaggio: Art, Knighthood and Malta, Midsea Books Ltd, Malta, 2006.

2 G. P. Bellori, Le Vite de’ pittori, scultori e architetti, ed. E. Borea. Turin, 1976 (orig. Rome, 1672). See H. Hibbard, Caravaggio, New York, 1983, p. 370.

3 For Caravaggism in Malta see eds C. de Giorgio, K. Sciberras, Caravaggio and Paintings of Realism in Malta, Malta, 2007.

4 For the documents see J. Azzopardi, “Documentary Sources on Caravaggio’s Stay in Malta,” in Farrugia Randon 1989, pp. 32–33.

5 The documents were first published in K. Sciberras: ‘Frater Michael Angelus in tumultu: the cause of Caravaggio’s imprisonment in Malta’, in The Burlington Magazine 144, 2002

6 See, for example, K. Sciberras, Riflessioni su Malta al tempo di Caravaggio, in ‘Paragone’, Anno LII N.620 Terza Serie 44, 2002.

7 See J. Azzopardi, “Documentary Sources on Caravaggio’s Stay in Malta,” in Farrugia Randon 1989, pp. 38–39. See also E. Sammut, “The Trial of Caravaggio,” in The Church of St. John in Valletta 1578–1978, ed. J. Azzopardi, exh. cat., Malta, 1978, pp. 21-27.

About the Author

Keith Sciberras, Ph.D., is Senior Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Malta. He has published extensively on the subject of Caravaggio, Roman Baroque sculpture and Baroque painting. he is the recipient of an Andrew W. Mellon Senior Fellowship in the Department of European Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and has been awarded the National [Malta] Book Prize for Research (2006). His publications include: Roman Baroque Sculpture for the Knights of Malta (2004);Caravaggio, Art, Knighthood, and Malta (2006; with David M. Stone); Melchiorre Cafà: Maltese Genius of the Roman Baroque (2006; as editor); Caravaggio and Paintings of Realism in Malta (2007; as co-editor); and several articles in leading international journals, including The Burlington Magazine and Paragone Arte. Dr. Sciberras contributed to numerous international research projects and exhibitions, including the milestone Caravaggio: The Final Years (Naples-London, 2004-2005). He has lectured in major Universities, Museums, and Art Institutions in Europe and USA.