The Art of Intemperance

With his riotous temperament and troubled life, Caravaggio seems to perfectly embody the myth of the rebellious genius, a quality that he shares with other great talents from the worlds of art, literature, film and music.

In modern and contemporary culture we have plenty of enfant terribles exemplifying this fascinating combination between insanity and genius. Back in 19th-century France, les poètes maudits, such as Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, were poets whose life and art went against their own society: their lives were often affected by the abuse of drugs and alcohol, insanity, crime and violence, while their poetry explored sacred and profane love, melancholy, corruption, and a complex imagery of senses and fragrances.

In narrative, a major example of brilliant long-suffering artist was Fëdor Dostoevskij, one of the most prominent figures in world literature, whose brooding, tortured characters, agonizing over existential themes of spiritual torment, religious awakening, and psychological confusion, were styled on his own life: besides his epileptic seizures, he also suffered from a serious gambling compulsion. Apparently, his masterpiece Crime and Punishment was written in a hurry because he was in need of an advance from his publisher, being left practically penniless after a gambling spree.

In contemporary art, the “bad boy” par excellence is perhaps Jean-Michel Basquiat, the postmodernist, neo-expressionist painter greatly influenced by the master of Cubism Pablo Picasso. Called “The Radiant Child” by the poet and artist Rene Ricard, he died of a heroine overdose in 1988, at the age of 28. Before him, a major figure in the abstract expressionist movement, Jackson Pollock, combined fame and notoriety with a troubled life, struggling with alcoholism his entire life until he died in a single-car crash at the age of 44 while driving under the influence of alcohol.

The history of music has also been made by a series of revolutionary rebellious characters, from Robert Schumann to Miles Davis, up to Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain, who once said: “I bought a gun and chose drugs instead.”

More than all the other arts, the film industry has drawn from the lives of these “anti-heroes” to consecrate a series of immortal legendary figures: James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, Steve McQueen and Marlon Brando. “Live fast, die young, and leave a beautiful corpse,” said the protagonist of A Rebel Without A Cause.

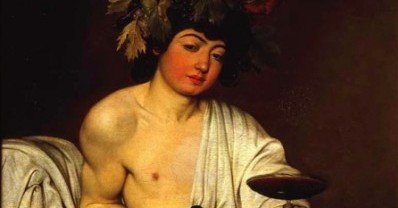

But where does the myth of the “cursed artist” come from? Such an inborn inclination to dissoluteness and intemperance is probably related to the “Apollonian” and “Dionysian” nature of art itself, with its dichotomy of light and darkness, harmony and discord. To better understand the great “tragedy” of the artistic temperament we should go back to the ancient Greek myths. It is no coincidence, in fact, that Parnassus – the home of the Muses and therefore of poetry, music and learning – was sacred both to Apollo, the god of the Sun, lightness, music and poetry, and to Dionysus, the god of wine, ecstasy and intoxication. The aesthetic usage of these mythological concepts is famously related to Friedrich Nietzsche, who, in his book The Birth of Tragedy, claimed that the summit of artistic creation is based on the fusion of opposite impulses: thinking and feeling, rational and irrational instincts. After all, what is art if not the struggle to make order out of the chaotic experience of everyone’s life?