A New Eye on Caravaggio

What makes Caravaggio so attractive for thousands of admirers today is his combination of emotionally appealing paintings and his violent and – for some – sexually deviant, perhaps even repellent personality. He does not to match our concept of “normal”, i.e. moral coherence of personality, public behavior and work.

This sex-and-crime constellation does not take into account, however, that we are mentally distant from the years around 1600 in Rome, when most people contended with at least two conflicting systems, that of religion and that of social honor. Despite the fact that Church of the Counterreformation tried to eliminate the latter in order to control both moral and legal affairs (their efforts at modernization) were not quite successful. Those who most opposed the delegation of honor and its defense to a centralized State were the old Roman nobility, the most violent group in Roman daily life, though this did not prevent its representatives to be members in charitable religious brotherhoods or participate in public displays of religious observance, for instance, the ritual of washing the chapped feet of pilgrims arriving in the Holy City. An ambitious middle class imitated this behavior. Caravaggio was part of this class: He was socially ambitious like most artists of his time and probably keen on becoming noble like many of his colleagues who had been awarded a knighthood. All his legal records reveal cases involving honor. Those who committed these deeds with, against or independently from him, were advocates, librarians, papal accountants, artists, nobles. Many of them had relations to one or more courtesans, (in Caravaggio’s case we know for sure only of one), and/or with under age young boys –“bardasse” (this is not firmly proven for Caravaggio) – be it before or during matrimony. There was no such thing as a homosexual identity, and eroticism fluctuated between male and female, between sacred and profane, as literature of the time reveals. A love madrigal could be read as sacred by changing one or two words and vice-versa, and the same is true for the music accompanying it. Readers and listeners took delight in finding out the subtle lines between ”amor sacro” and “amor profano” (also a much-appreciated subject of painting in the time.

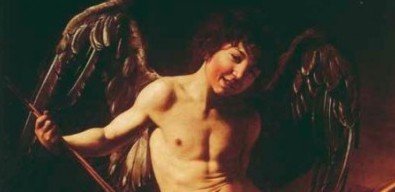

One of the most appreciated aspect of art was the wonder – “meraviglia” or “stupore” – that it would make one experience. At the time, the way to religious meditation was through sensual perception. This was not questioned by the Church, which required painters to move the spectators in a credible way, i.e. to move their senses like a real event would. Caravaggio’s paintings met all these requirements. In cases in which his works were intended for private connoisseurs, he integrated sophisticated references to art itself, thus adding intellectual pleasure to religious meditation. Most, if not all of his collectors were following a “new” and fashionable religious practice that required practitioners to be aware of the sacred within humble daily activities, and Caravaggio himself was educated in this practice since childhood. His religious paintings show a connection to this. In some of them, his inclusion of a self-portrait as a witness to the holy event is not faithlesslessness. Any attempt to define his psychology must remain purely speculative; the documents do not really tell us much, and even Sigmund Freud could not help to bridge the mental difference between our times and his.

Caravaggio’s paintings were successful in offering what all his artistic peers considered to be the highest achievement of painting: closeness to nature in appearance and emotional credibility. His works provide delightful surprise through unexpected innovation more than any one of his contemporaries. His success was promoted by literary praise, and his fans slandered the works of his contemporaries. This was nothing new –Federico Zuccari, for instance, had experienced something similar 20 years earlier, but competition was particularly harsh in Rome around 1600, and the publicity that accompanied Caravaggio’s rise had a weightier quality. The legal proceeding instituted against him and his friends in 1603 by painter Givanni Baglione represented a struggle for market. It was easily observed that his fresh style contained aspects of Venetian painting, which was much en vogue with collectors of his day, along with use of light extremely diverse for Roman eyes. His techniques were a mystery. Documentary evidence suggests that he did not want his production process to be known – insisting that he studied nothing but nature. He probably did so in a very extensive way, including an observation of optical phenomena as presented by in scientific findings of his time. Coincidentally, they were discussed and eventually experienced in the house of his first important protector, Cardinal Del Monte, whose brother was a well-known mathematician. Soon after Caravaggio’s death, ideas about his methods were written down, since his paintings seemed like tableaux vivants painted directly from life, though this was never proven nor stated directly as fact in sources. Half a century after his death, however, this was taken for granted by Giovan Pietro Bellori: time had changed conspicuously in terms of religious practice and artistic ideals. A painter who simply copied nature – as it was now generally assumed that Caravaggio did – was a minor painter, even one who diminished the real art of painting. Bellori relied on the first printed biography of Caravaggio, which was written by the artist’s enemy, Baglione, long after the artist’s death. Baglione insinuated – but nearly never asserts directly – that Caravaggio’s religious paintings had been rejected; he often distorted events that documents prove to have occurred otherwise. Bellori added his own reason for the rejection of his works: too much humble daily life pictured within elevated, sacred stories. Ideas about devotion had clearly changed by that time, and the process of unifying people’s moral identity had shifted too: it was accepted that a bad painter would likely have a bad temperament.

Most people and many art historians still believe in the unity of personality and artistic work. Although this may often be the case, especially since Romanticism, it is a topical construction. Looking at Caravaggio’s paintings, we perceive a highly intelligent artist, carefully respecting the culture of his patrons and dialoguing with them through visual means. This implies a careful preparation of his compositions. A comparison of figures assumed to be direct portraits of models reveals that in fact he transformed their appearance. Quite a number of his works could not have been made from living arrangements in the studio, for plain technical reasons. Most painters studied living models, and he surely did so, too. Since he left no drawings, we must admit that we still do not know how he transposed what he had studied. But even today, the results of technological investigations and restoration campaigns are easily interpreted as traces of the production process as Bellori presented it. The same is true for the apparent hastiness of his late paintings, taken as a proof for his sense – and reality – of being hunted for committing murder. In fact, he committed an accidental homicide, in a fight that involved four persons on each side. Since death in this way occurred relatively frequently at the time, he had a good reason for expecting pardon. Nothing proves that he felt especially guilty or that he had been persecuted. His late technique – as one unprejudiced restorer has noted – aims at looking quick and painterly, but in fact required much more time than its appearance suggests. He was thus a pioneer in a technique which would have a wide effect in 17th century painting, be it as “rauwe manier” in the Netherlands or “fa presto” in Italy, as a proof of virtuosity.

And so, what if (for the sake of art historical methodoloy), for the 400th anniversary of his death, we tried to eliminate everything not directly proved by contemporary documents, instead reading them for their intrinsic value (the testimony of an enemy at court may be a defamation, for instance); what if we tried not to speculate about his personality with our modern psychology, and tried to overcome what later generations have said about him (and perhaps successfully convinced us). In short, what if we were not pre-conditioned by what centuries have built up about the artist? Some might say we are destroying a myth. Perhaps, but scholarship is no mythology, and revisiting primary sources, we discover something better: a genial and intelligent artist. And forget about his intimate life details – we simply do not know enough about it factually. His works do not tell us about it either, instead they show a sophisticated, unprecedented art.

About the Author

Sybille Ebert-Schifferer is Director at the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max Planck Institute of Art History, Rome, since 2001. She studied art history, musicology, and theatre history in Munich and Berlin. After having worked as Head of Exhibitions at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, where she curated, among others, exhibitions on Guido Reni and Guercino, she was appointed as Director of the Hesse State Museum in Darmstadt in 1991 and as General Director of the Saxon State Art Collections in Dresden in 1998. She taught at the universities of Frankfurt, Bonn and Dresden, and was guest curator of the exhibition on trompe-l’oeil, Deceptions and Illusions at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, held in 2002/2003. She has recently (2009) been Summer Fellow at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown (Mass.). Among her publications are Still Life: A History (New York, Abrams 1999) and numerous articles on Italian, but also French and German Art of the 16th – 18th century. In September 2009, she published the monograph Caravaggio. Sehen – Staunen – Glauben (C. H. Beck, Munich) which is now in its second edition and has been translated into French (Caravage, Hazan, Paris 2009).