A Brief Meditation On Italian Photography

Medium for a visual culture

Given the impressive cultural heritage on constant display along the length and breadth of the peninsula, it seems almost banal to say that Italian culture is highly visual. Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374), considered to be the first “modern” intellectual, gives an unprecedented, detailed description of the human eye as an instrument of visualization and encoding in one of his poems that is as “technologically” accurate as any contemporary description of a photo camera might be today.

As my recent book Looters, Photographers, and Thieves: Aspects of Italian Photographic Culture in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (2011) suggests, whether we are talking about Italian fashion, design, architecture, or the long list of visual artists classical and contemporary, the seduction of the visual plays a central role in Italian life. Photography, as a relatively young medium, has evolved by leaps and bounds and is now available in myriad digital formats that go from laptops, to tablets, to phones, to pen-cameras. While it has become all-important in documenting everyday life, its cultural legacy in Italy has been to provide a visual vocabulary for what has come to be know as italianità. Whatever one’s feelings regarding this essentializing expression of national traits, it is enough to say in this context that it represents a set of parameters championed by some and contested by others since the birth of the Italian nation. It is therefore important that photography was put at the service of this task soon after Unification by a number of individual photographers and agencies, among which the most important is arguably that of the Fratelli Alinari. Theirs is a particularly important contribution at a time when Florence was, for a short time (1865-1871), capital of the nation.

That so many of our writers, among them Italo Calvino, Leonardo Sciascia, Vincenzo Consolo, Gianni Celati, and Lalla Romano, with her “photographic novels”, have at some point written about photography is a further indication of the Italian fascination with figural representation and its creative potential. At an earlier time, other writers, engaged in an attempt to represent their most immediate social environment through what we know as Verismo and Realismo, took up photography as a parallel activity to their writing. Giovanni Verga and Luigi Capuana, for example, exchanged ideas about photography’s representational possibilities, as well as on the medium’s value for their “realist” writing.

This penchant for the visual, well-represented throughout the breadth of Italian cultural history, easily suggests that Italian culture is convincingly visual. The popular expression fare bella figura (to cut a beautiful figure), provides a useful entry-point through which to consider the importance of appearances in the context of national discourse, both in a supportive role to the emerging nation in the late 1800s as well as in today’s Italian self-imaging. It is in such occasions that photography reveals its complex role as an instrument of social practice.

The Alinari Archives, by far the most extensive private photographic archive of major national importance, were in large part responsible for the elaboration and maintenance of a national image. Their cataloguing of landscapes, art treasures, architecture, and the diverse customs and populations of the peninsula is unparalleled. Alinari photographs helped define Italy in the imaginary of Grand Tourists, as testified by their inclusion in many travel books and their mention in literary texts, such as in E. M. Forster’s Room With a View.

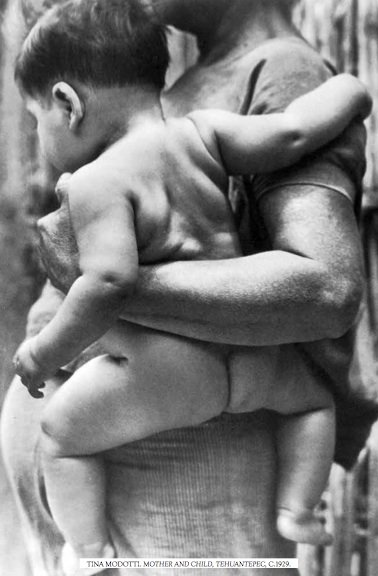

Contemporary Italian photography lists many names that represent the variety of uses of the medium. Fashion photography, advertising, fine art, are all well-represented, and of course any list in a limited space such as this is bound to exclude too many names. Gabriele Basilico, Letizia Battaglia, Luca Campigotto, Franco Fontana, Luigi Ghirri, Mimmo Jodice and Enzo Sellerio comprise a very short list. To this I would add the influential name of the more globally known Mario Giacometti, and those of two contemporaries of the Alinari, foreigners who lived and worked in Italy, Giorgio Sommer and the Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden. To these, the name of another well-known and influential photographer must be added, Tina Modotti. Modotti, an Italian expatriate who lived most of her life abroad in the U.S. and Mexico, and produced most of her photographs in the latter, stands at the pinnacle of photographic history despite her short career.

Mimmo Jodice and Luigi Ghirriare are representative of a photography that explores the artifacts of human habitation, past and present. The Neapolitan Jodice states that “at the end of the seventies my relationship to the city changed. My uneasiness became internalized and became a silent protest. My photographs showed an empty and rarefied city and the people, who were once central to my photography, disappeared.”1 Ghirri’s lens is cast on the abandonment of the lived environment to itself, in a search for previously unseen suggestions regarding the artifacts of human culture.

Finally, Italian photography evolves through the ages from a simple tool of artistic experimentation, to a tool of social transformation and definition, to an instrument of anthropological documentation and classification, to one of activism and artistic expression. The Sicilian photographer Letizia Battaglia, whose main body of work includes the documentation of the ills of the city of Palermo and the infestation of its social, political, and cultural spheres by the Mafia, makes a case for the panoramic view that photography provides. “A me interessano in genere i Sud del mondo” (79),2 offers an insight into how casting our gaze on the local might offer a way in which to see the world around us through the lens of the familiar.

1 Jodice in Lo sguardo dal Sud, Mauro. p. 22

2 ibid., p. 79.

About the Author

Pasquale Verdicchio teaches Italian film, literature & cultural studies in the Department

of Literature at the University of California, San Diego. As a translator he published the works of Pasolini, Merini, Caproni, Porta, and Zanzotto among others. His own writings of poetry, reviews, criticism, and photography have been published in journals and in book form by a variety of presses. His books include Devils in Paradise: Writings on Post-Emigrant Cultures (Guernica Editions, 1998), Bound by Distance: Rethinking Nationalism through the Italian Diaspora (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008), and Looters, Photographers, and Thieves (Fairleigh Dickinson, 2011); his most recent poetry collection is This Nothing’s Place, which was awarded the 2010 Bressani Prize. He is the recipient of several grants including the California Council for the Humanities for research in the preservation of Italian history and culture in San Diego. He is also a founding member and Vice President of the San Diego Italian Film Festival.