Food as a literary and political icon in Italy

Italian novels and non-fiction have always been spiced with an abundance of culinary references. Far from being a mere descriptive element contributing to realistic representation, food is a significant narrative ingredient in both classic and contemporary literature, enriching it with anthropological, psychological and sociological “flavors.”

In his Divine Comedy (1304-21), Dante Alighieri refers to bread to allude to the inherent bitterness of exile (“You are to know the bitter taste of others’ bread, how salty it is”), while Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (1348-53) nourishes our imagination with culinary excesses to describe a fictional country, Bengodi, “where the vines are tied up with sausages,” mountains are “made of grated Parmesan cheese” and rivers flow with white wine. Food seems to have an ethical and ideological function in Alessandro Manzoni’s I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed, 1827), but its physicality becomes prominent in Giovanni Verga’s I Malavoglia (The House by the Medlar Tree, 1881), contributing to the powerful verism of depictions. Culinary signs lose their material dimension in the aristocratic settings of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s Il piacere (1889, The Child of Pleasure), acquiring a more aesthetic and erotic value, and become a tool for criticizing the emptiness of bourgeois society in Elio Vittorini’s allegorical novel Il Sempione strizza l’occhio al Frejus (The Twilight of the Elephant, 1946). A tragic symbol of deprivation and hope in Primo Levi’s Se questo è un uomo (If This is a Man, 1947), food takes center stage in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s Il Gattopardo (The Leopard, 1958), one of its most memorable scenes revolving around a famous “timballo di maccheroni.” In Carlo Emilio Gadda’s experimental prose, it is a further element of encyclopedic and baroque accumulation, whereas in Italo Calvino’s Sotto il sole del giaguaro (Under the Jaguar Sun, 1986) it is a starting point for a compelling journey through senses, becoming a metonymy of the world.

If Gian Paolo Biasin, in The Flavors of Modernity: Food and the Novel (1993), considers food as “a heuristic tool for the readability of the world,” Carlo Petrini turns it into an instrument of liberation, investing it with an unprecedented political value.

His new book, Food & Freedom, How the Slow Food Movement is Changing the World through Gastronomy (2015), calls for a battle of civilization against the “wasteconomy” to be waged with the weapons of gastronomy. Through his Slow Food organization, which has so far gathered over 100,000 members from 150 countries, Petrini has actually “unpaired the cards” on the world table, claiming respect for small-scale agriculture, local gastronomies and biodiversity.

Arguing against an antiquated model of gastronomy that “champions an elitist approach to the enjoyment of food” and forgets the farmer, he collects memories and first-hand observations on innovative approaches to food problems all around the world. The pervasive presence of food in TV programs is fiercely condemned as “pornography”: “Food on TV is pure show biz, with competitions between cooks that boil down to a race against the clock: recipes that have to be thrown together in a few minutes for the husband just home from work who wants to watch the news; restaurants that are madhouses in which chefs alternate excesses of rudeness and seductiveness.”

Subverting Mao Zedong’s famous quip, “Revolution is not a dinner party,” Petrini claims that “revolution can be a table set for dinner, be it real or metaphorical,” and launches an uplifting message: if people can feed themselves, they can be free.

Whether it is a literary or political device, food is indeed a valuable magnifying glass to analyze the evolution of our culture and society and have a “taste” of our collective identity.

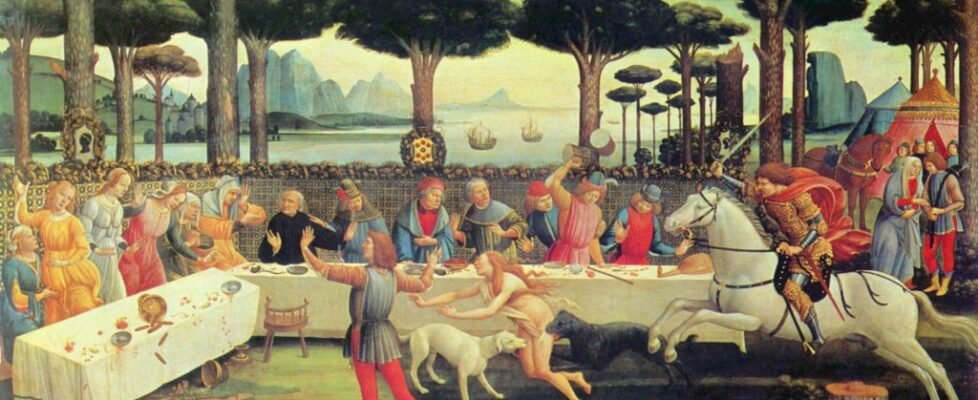

The Banquet in the Pine Forest (1482-3) is the third painting in Sandro Botticelli’s series The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, which illustrates events from Boccaccio’s Decameron.

The Banquet in the Pine Forest (1482-3) is the third painting in Sandro Botticelli’s series The Story of Nastagio degli Onesti, which illustrates events from Boccaccio’s Decameron.