“And Yet It Moves…”: The film Galileo represents the neverending struggle for scientific freedom against all forms of censorship

A yearly appointment not to be missed by film critics and moviegoers from all around the world, the 66th edition of the Venice Film Festival confirms itself as one of the most prestigious events in the film calendar, with a rich and variegated selection of international titles and the ever-present parade of stars and celebrities.

This year, the festival has dedicated special attention to issues related to war, immigration and global crisis, awarding the Global Lion for best film to the intense and claustrophobic Lebanon, by Israeli Samuel Maoz, which is entirely set inside a tank where four young inexperienced Israeli soldiers strive to survive during the 1982 war in Lebanon. The festival’s second prize, the Silver Lion for best director, was instead awarded to feminist Iranian artist Shirin Neshat, for her striking film Women Without Men.

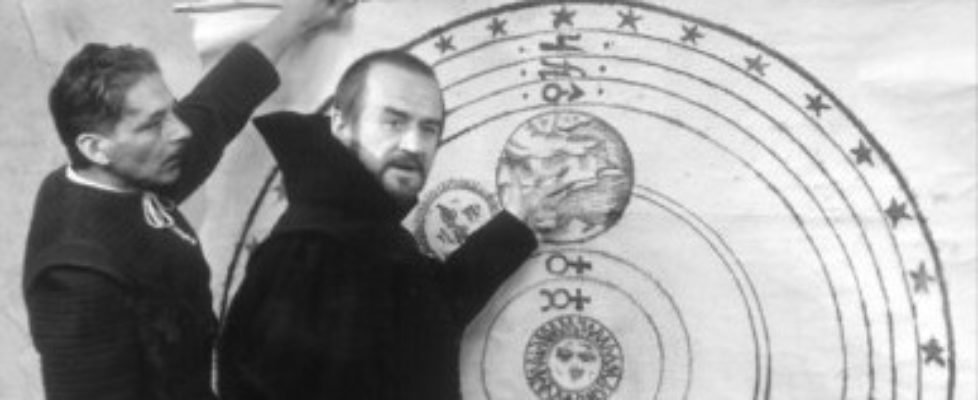

Beside the major sections of the festival, the retrospective section evocatively named “These Phantoms” has shed a light on some lost masterpieces of Italian cinema. Among the titles included in this section, there is also Galileo (1968), by the celebrated Italian director Liliana Cavani. The film has been restored by the National Film Archive of the Experimental Cinematography Centre in Rome, and, after over 40 years, reopens the age-old debate about the relationship between faith and science.

Shot in Sofia, Bulgaria, the film retraces the story of Galileo Galilei, starting from the early years of his scientific career at the end of the 16th century, when he moved to Padua to teach Physics at the University. This is where Giordano Bruno’s heretical ideas and the sun-centred Copernican theory began to take shape. Through lengthy studies, Galileo became convinced that it is the sun, and not the earth, that is at the centre of the universe. When summoned to Rome to defend himself against the accusation of heresy, he was asked by Cardinal Bellarmino and the Pope himself to defer his studies and was compelled to forswear the Copernican theory in which he had firmly believed.

First presented at the Venice Film Festival in 1968, in the year of the student protests, the film experienced itself the kind of censorship it portrays. Italian state television RAI refused to broadcast the film, as it was considered too anticlerical and therefore politically dangerous. The film was also banned from movie theatres, due to the refusal of Angelo Rizzoli to distribute it, and was condemned to oblivion. However, over all these years, the memory of such a revolutionary and controversial work has been kept alive by courageous teachers, who have continued to show the film to their students, also thanks to the large circulation promoted by the Catholic distribution company San Paolo Film in the schools. Needless to say, the history of the cultural life of a country is sometimes made of unpredictable paradoxes…

«That’s how the world goes» – commented Liliana Cavani introducing the screening of Galileo to the Festival’s audience – «Time passes by, and yet the world is still the same. That’s why Galileo’s story is still relevant today». As the director points out, «while carrying out his first telescopic observations, Galileo believed that the discovery of the truth could be of use to the Church in the first place, and therefore he sought a dialogue with the ecclesiastical hierarchies. When he appeared before the Holy Office in Rome, he was convinced that he would eventually wear down their resistance, but he was going to be bitterly disappointed. That was a time when the Church exerted complete control over scientific knowledge».

Seen today, 40 years after its production, the film keeps its extraordinary modernity, both in its content and stylistic features. The deepest meanings of the film seem to be conveyed more by scenic, architectural and visual elements than by the words. So, the sense of oppression of the hegemonic power is expressed through the predominance of bottom-up shots with the use of wide-angle lens. The rational attitude of Galileo’s mind is instead

conveyed through the abundance of geometric shapes and lines, whereas the verbose pompousness of clergymen is suggested by the profusion of baroque architectural elements. Despite such complexity of communication levels, the film develops its plot in the most straightforward and simple way, preserving its popular character, as in the spirit of Galileo’s lesson.

As the celebrated film critic Morando Morandini stated, «the film overturns nearly all conventional forms of biographical cinema and transforms the reconstruction of the past into action in the present. It is both the tragedy of a man who is ahead of his times and the story of naivety».

Moreover, Liliana Cavani’s Galileo has an additional layer of interest as a complex reflection of the never-ending debate over freedom and censorship, which is of particular concern in Italy today, considering the recent debates on the freedom of press and the status of democracy in our country (or better “videocracy”, as the Swedish-based Italian filmmaker Erik Gandini pointed out in the documentary film of the same name presented at the Venice Film Festival).

Liliana Cavani is no stranger to these kinds of topics, and her films have often raised rather heated debates. The characters she has always selected for her films are in fact troublesome, controversial or revolutionary in some ways. Before Galileo, she had made her debut as a film director with the feature film Francesco d’Assisi (1966), where the legendary figure of the Saint was depicted as a sort of hippy-like personage. The first films she directed for the cinema dealt with uncommon themes in that field, such as marginalization, mysticism and Nazism. She is best known for her 1974 feature film Il portiere di notte (The Night Porter), which launched actress Charlotte Rampling to international stardom. She conquered the international market with Interno berlinese (The Berlin Affair, 1985) and Francesco (1989), with Mickey Rourke playing the lead. After realizing the TV series Einstein for the RAI in 2007, in the last years she has devoted herself to the theatre.

When asked about the political relevance of her movies, she answers: «My films are not political in a strict sense. They go beyond the historical role of characters: they investigate the inner truth of human feelings». It is when these feelings concern the struggle for scientific freedom, against every form of censorship, that the story of a single man becomes the history of the whole mankind.

Laura Giacalone is the Associate Editor of the Italian Journal.