Exploring the legacy of Galileo in the year of Astronomy.

by Claudia PALMIRA

Galileo was a great marketer, said the head of the Medici Project Martha Mc-Geary Snider, when we met at the American Academy of Rome.

The swearing in of the new U.S. Ambassador to Rome, David Thorne, 64, marks new era for U.S.-Italian relations. Investor, entrepreneur, author and supporter of the arts, Thorne is the co-founder of Adviser Investments one of the U.S.’s top firms specializing in Vanguard and Fidelity mutual funds and exchange trade funds. He is a former President and current Board member of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston and led the design oversight team for its new building in Boston. Additionally, he has participated in a variety of other undertakings including marketing, consulting, and real estate.

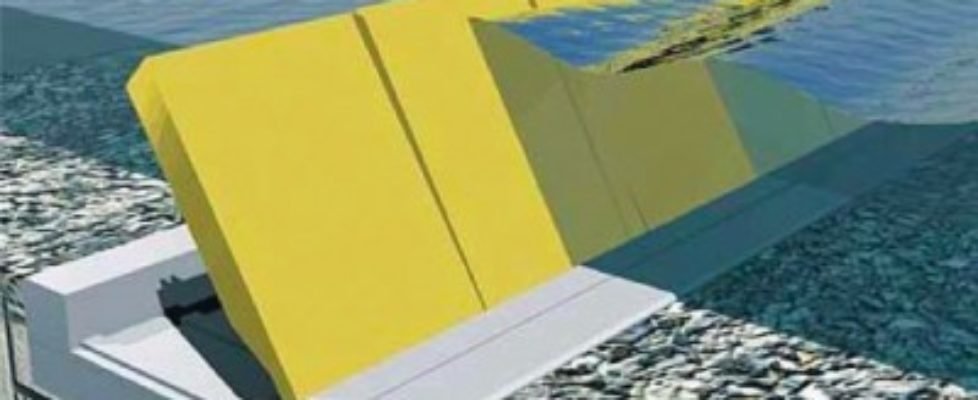

The fifth Annual Conference of the Italian Language Inter Cultural Alliance (ILICA) in New York was called: “Saving Venezia & Protecting New Orleans.” The leaders of the M.O.S.E. project (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico or Experimental Electromechanical Module) were in New York to demonstrate how the technology designed to save Venice can be applied to New Orleans. Here, Dr. Maria Teresa Brotto explains how this Italian high-tech project will work.

by Efthalia STAIKOS

As consumers, we fight a battle every time we enter a supermarket. Do we buy or do we not buy? Is it healthy or unhealthy? Will it be tasty or disgusting? A burden is placed on us to utilize the wealth of knowledge at our disposal so that we do not make ignorant decisions. Between the internet, books, and magazines about every topic imaginable, we become handicapped by knowledge. We assume we can trust food companies because clearly they would not trick us if it’s so easy for us to research into the truth about their products. The only problem is that this assumption makes us lazy and we do not end up doing our research. We trust that if a product says it is “Authentic Italian Tomato Sauce,” then it must be. Clearly the company would be penalized for lying. Unfortunately, this is not the case and we buy into food counterfeiting scams every day.

Samantha Cristoforetti became Italy’s first woman astronaut this year when a 32-year-old Italian Air Force pilot became the European Space Agency’s first female pick.

by C. BENEDETTI

Galileo Galilei, one of history’s most influential astronomers, may have started from humble beginnings, but by the end of his life he had produced some of science’s most significant discoveries.

by Piergiorgio ODIFREDDI

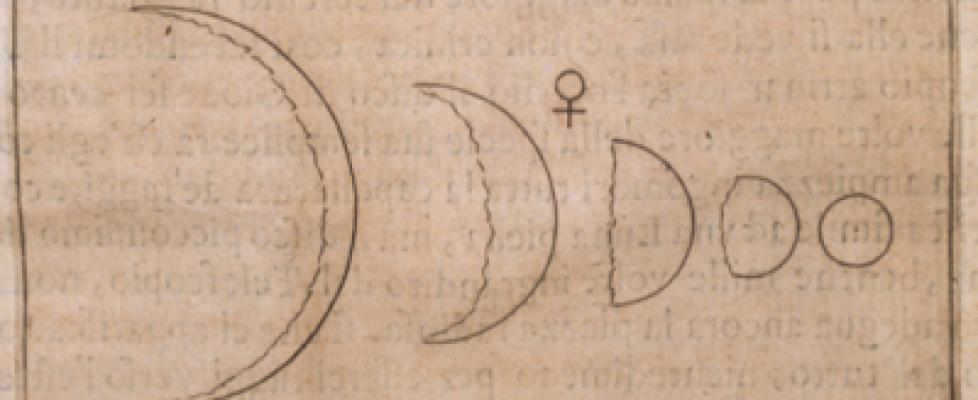

On January 7, 1610, Galileo wrote a letter to Antonio de’ Medici where he briefly reported on the results of his first observations of the sky through a telescope exactly 400 years ago, late in the summer of 1609. The letter concluded with some news of the day: “Only this evening I have seen Jupiter accompanied by three fixed stars totally invisible because of their smallness.” With understandable and justifiable pride, he also noticed: “We can believe to have been the first in the world to discover something about the heavenly bodies from so nearby and so distinctly.”

by Mario BIAGIOLI

Modern scientists have become increasingly aggressive in protecting their intellectual property by patenting their discoveries and, sometimes, by keeping them secret. Galileo anticipated this trend.

by Matteo VALLIERIANI

The interested reader may have noticed how historians in recent decades have attempted to deconstruct the identity of Galileo Galilei. He is no longer just the great astronomer or even just the founder of the modern experimental method in science. Even the political value of his work and his life, systematically reconsidered in the frame of the debates about the relation between Church and research institutions or between religion and science, is no longer the single relevant perspective for approaching this kind of historical thread. Thanks to the work of historians of science of the last twenty years, readers are now used to very different interpretations. Galileo is now also a heretic, a revolutionary martyr, a mathematician, an Aristotelian natural philosopher, an artist – almost with brush and palette in his hand – and finally a gifted courtier. This, however, is only an apparent process of fragmentation. Historiographically speaking, a process of this kind tends to cancel categories such as “genius” from scientific activities and their histories. Such categories are used to justify the impossibility of explaining historical phenomena. In other terms, the actual history of science requires science and its history to remain rational activities. For this reason, it is relevant to undertake an investigation of Galileo in all of his contexts.

by Paolo PALMIERI

When Galileo Galilei was a student at the University of Pisa in the 1580s, physics was a loose bundle of ideas inherited from the Greeks, mostly from the philosopher Aristotle, via the mediation of the Latin Middle Ages. Projectiles keep going after being released by their projectors because air keeps pushing them for a while, as the most in vogue theory of the time would have it (though there were variations). Theirs is a violent motion. Heavy things fall downwards because the centre of the earth is the natural place for them to achieve their natural state of rest. Theirs is a natural motion. Pendulums are constrained motions. Is the motion of a pendulum violent or natural? Why does it turn back after reaching a summit? Why do violent motions such as those of cannon balls cease? These were the questions a professor of physics would investigate at that time.